Executive Summary

Many Government Contracting Officers and IT program managers believe that the Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR) inhibit or prevent agencies from allowing the use of innovative technologies and techniques in acquiring agile development services. This is not true. In fact, the FAR encourages innovations such as the Agile approach, allowing agencies to change direction in collaboration with their vendor after both learn lessons from experience and customer feedback received during early phases (sprints) in their major IT modernization projects. This paper describes the details of how the FAR supports Agile and suggests that acquisitions should be considered successful based on whether benefits have been received from the eventual implementation of the project – not from simply selecting a vendor and awarding a contract to start the project.

Part I: Introduction

It is not uncommon in acquisitions of information technology that typical standard federal agency procurement practices fail to yield the intended results. A common complaint is that the final product the government receives is quite different than what it envisioned at the beginning of the acquisition process. Why? Is it possible for the government to implement better acquisition practices that yield better results and still work within acquisition regulations? As a corollary, how can it be done without greater risk of protest?

This article will consider these questions from a “reverse planning” approach that starts by emphasizing the envisioned outcomes. Additionally, we will show how this approach presents a lower risk when viewed in the context of achieving the purpose of the acquisition. We’ll examine how some non-traditional acquisition approaches are compliant with federal acquisition regulations as well.

To successful capture the value from Agile, the Government must be willing to change in three different ways. The first change should be in the perspective. When procuring agile services, the Government should recognize that they are not acquiring a system, but services. This is the most frequent unspoken assumption in systems acquisitions. (Before the advent of Agile software development, Waterfall was the default methodology. Drafting the Systems Requirement Document (SRD) for a Waterfall acquisition was a difficult and time-consuming process. By the time a contract was awarded, so much had changed that it was not unusual for the Government and Contractor to immediately begin making changes and negotiating revised cost estimates.) In Agile, it is more important to obtain the services that will eventually deliver a system that provides the greatest value to the Government at contract completion over delivering comprehensive and convincing proposal documents. It is about Show-Me instead of Tell-Me. “Tell me” – the traditional written proposal and waterfall approach – describes a binding end result (of which, while “Show me” proves the efficacy of the service and people).

The second change in perspective essential to a successful acquisition is to start viewing Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR) as the gateway to success instead of a roadblock to using innovative techniques in acquisitions. The FAR actually promotes innovation! Later in this article, we will show how many in the Government currently misinterpret the FAR and, as a result, do not fully take advantage of all the potential tools and techniques that are already available through innovations in information technology.

Finally, the third change is that Contracting Officers must change their perspective on risk. Contracting Officers need to adopt the perspective that the greatest risk to the Government is that once a contract is complete if the Government does not have a successful program, the Government has wasted both time and money at the expense of the taxpayer. Program failure is the greatest risk. The downside risk of using innovative techniques is much smaller in comparison to program failure.

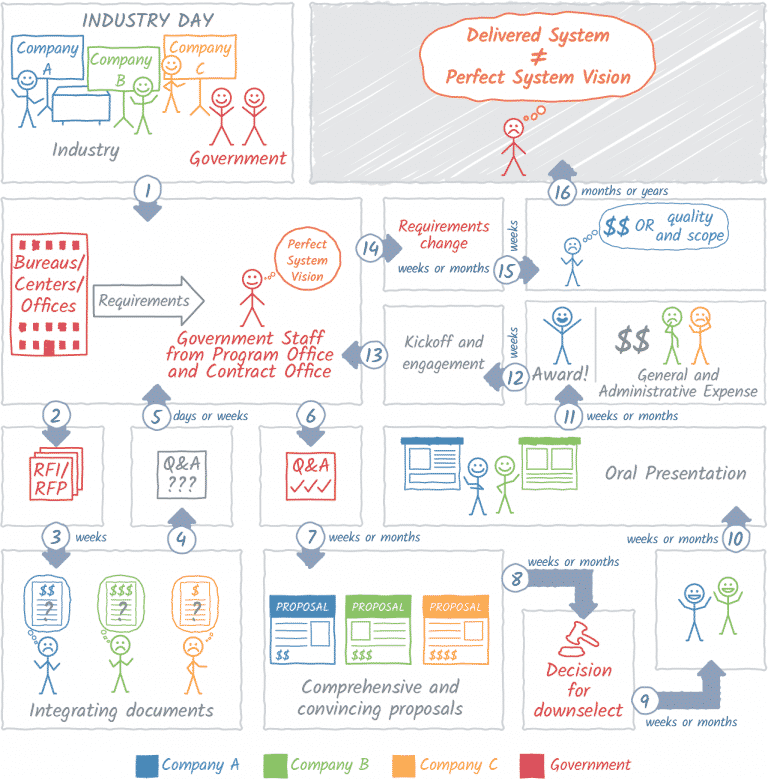

The change in perspective starts with a review of current commonly used acquisition activities to honestly assess their effect. In a standard acquisition, there are some market research activities such as a Request for Information (RFI). Then, there may be a pre-solicitation conference where the Government talks to industry about the acquisition and answers questions. Then, there might be a draft Request for Proposal (RFP) followed by more written questions and answers, followed by the actual RFP with more questions and answers. After receipt of proposals, there is usually a written discussion with offerors.

There are unfortunate consequences of this process:

- Written documents are subject to interpretation (and misinterpretation) by the reader.

- It is difficult to adequately convey the Government’s vision in writing. Even good writers find it a challenge to put their vision into words.

- If the requirements are not clear or are interpreted differently by different members of industry, the estimates to perform the work will be flawed or inconsistent.

- The written question and answer cycle is not always helpful, because the written Government response may be misinterpreted as well.

- Compiling all these documents and responses takes time, slowing the acquisition and decision-making process.

- All the time and energy to create these documents has little usefulness to either the Government or contractors after award. Most programs are very different at implementation (compared to the vision when acquisition is starting) due to changing circumstances and time delays on the first day of execution.

- Due to misinterpretation of the Government’s vision and intent in the acquisition, the Government may not end up awarding a contractor who can provide the best value. They end up awarding it based only on written responses, which only proves one contractor can write a better proposal. It doesn’t mean they can perform better.

- Rarely do the written acquisition documents define the metrics for success of the program.

- Due to the length of time and the self-inflicted documentation requirements, there is an increased cost of acquisition for both government and contractors. The cost that contractors incur is charged back to the Government through General and Administrative (G&A) expense pools. Multiplied across the entire Government, the cost of doing business this way is staggering.

Agile software development’s benefit is that it does not attempt to define the final system requirements at the beginning of the process. It allows for shifting needs and wants of the end user. To further improve the probability of success, the Government could structure acquisitions to obtain services from a contractor who not only knows Agile software development but can assist the Government in the process of envisioning the end product. Contractors that don’t understand what the Government considers success will not be able to advise how to achieve it and deliver impactful results in each sprint.

Figure 1: Current Acquisition Process and Problems

All this may sound very sensible and reasonable. However, it prompts the question: Why does the Government repeat this process, when it can’t clearly demonstrate each and every time that its contracting officials successfully procured exactly what was desired? Does the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) hinder any hope for success or need revision?

Not exactly. The acquisition reforms envisioned under the Federal Acquisition Streamlining Act in 1994 and Federal Acquisition Reform Act of 1995 was brought about precisely to help the Government to acquire products and services in ways more akin to those used by private businesses, and to better ensure the best use of taxpayer funds. Before these Acts, there was no concept of a “best value” acquisition. Agile software development was an unknown concept as well. However, the changes brought about by those Acts were not meant to deter innovation in acquisition. In fact, the Acts themselves were a great evolution in Government acquisition reform. The question is how far they were meant to be taken? Is the use of technology and communications over the nearly quarter century since the FAR was rewritten outside the intent of the reform? Or, were these Acts ahead of their time and meant to be viewed in light of their intent? We’ll review the applicable FAR citations, using examples of some current technologies to demonstrate that the FAR is not opposed to the use of new and innovative technologies in the acquisition of IT systems or services.

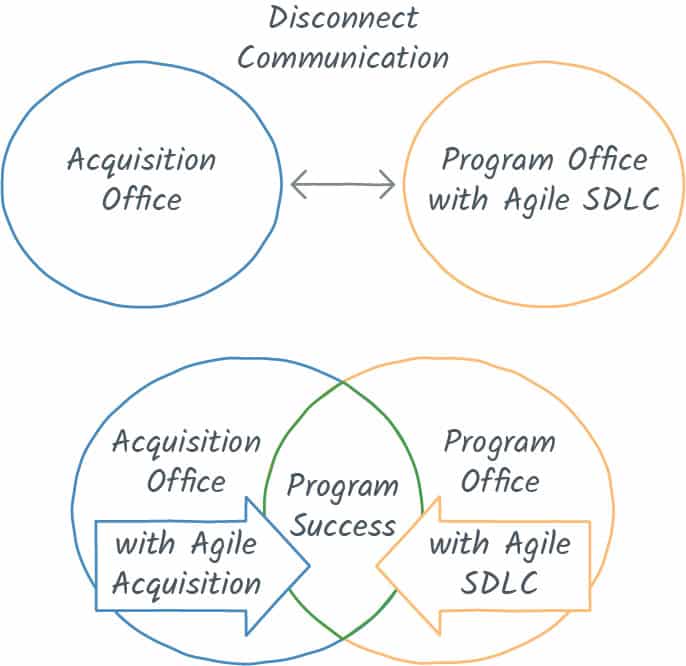

Figure 2: Existing Acquisition state and Agile Acquisition

There are unique contracting challenges that Government and industry both must address in purchasing and delivering Agile software development services. However, none of the challenges negate the need to revisit the acquisition process and implement innovative techniques using available IT tools to improve contractor performance. That is addressed later in this article.

Part II: Reverse Planning – Start to End

A new perspective on systems acquisition is needed from start to finish – literally. It sometimes seems as if the procurement phase and the contract performance phase are two disconnected processes. Once a contract is awarded, the acquisition staff are done and can get back to their day jobs. It’s now the program office’s job to oversee the work! Perhaps there will be some interaction between them during performance, but it’s not common unless there is a problem.

It may benefit agencies to designate certain Contracting Officers as subject experts on Agile.

It would enhance the success of the system acquisition if it were viewed as a holistic process from the end state all the way back to the acquisition planning stage. By taking a holistic view, the Government starts by clearly describing what the successful acquisition looks like when it is done instead of simply describing the steps that should be taken. The usefulness to the Government upon completion should drive the decisions and help the Contracting Officer to view the acquisition by the Agency’s ability to meet its mission, not by solely awarding a contract. A good process envisions the Contacting Officer to have more engagement throughout the contract life cycle. Since the sprint cycle of the Agile approach has much shorter steps, there are more opportunities to ensure contractors are performing as expected. Many times, Contracting Officers are only engaged during performance when there is a problem or a change to the requirements. They should also be engaged when the program is succeeding so they have greater insight into how quality contractors perform Agile development.

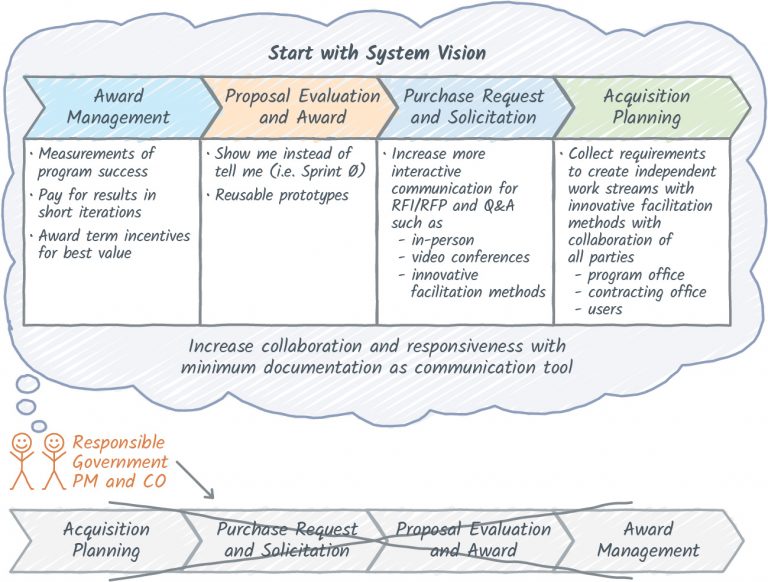

The Contracting Officer should be engaged on what the end state looks like as well. One way to help drive the vision of what the successful outcome of the acquisition is to play a reverse planning game called “Remember the Future.” In this exercise, the participants imagine that it is sometime in the future and that they’ve been using their envisioned system almost continuously between now and that future date (it doesn’t have to be 5 years). After this initial step, start imagining it even farther into the future (months or years later). The participants then write down, in as much detail as possible, exactly what the system will have done to make them successful in achieving their objectives.

This exercise helps define success at the end of the acquisition process. If everyone, including the acquisition contracting officer, agrees on what success means, it will drive actions toward that end. This process may be compared to swimming in the open water toward a specific spot – it helps to lift your head out of the water frequently to see if you are on track.

Figure 3: Agile Acquisition Start from End

The result of this exercise should not be filed in a drawer once is complete. Share it with industry! What’s the risk? The envisioned success might be achieved! Consider inviting industry to participate in the process so vendors get a more in-depth understanding of how to achieve success in performing the contract.

As discussed earlier, the goal of this process is not to perfectly define the finished product in the pre-RFP phase, only what program success looks like. A System Requirements Document (SRD) is not the deliverable at the end of the reverse planning process. The problem with a SRD is that both the Government and industry are committed to delivering those requirements regardless of whether they add any value or continue to be relevant. Additionally, revisions to the SRD mean that that there will likely be cost increases and schedule delays due to the negotiation process. Traditional systems acquisition always involves the classic “scope, schedule, and budget.” If any one of these changes, it absolutely impacts the other two (usually not in the Government’s favor). The best way to avoid this situation is to only describe what success looks like from a high level in concrete measurable terms, but not cling to those terms. Agile development favors the incorporation of new requirements. It works best when the outcome is measurable in meaningful terms. For example, the new system will reduce the time it takes to perform X process from __ days to __ days, which will save the Government $$ per year.

Let’s not stop there! Since the process now has a clearly defined outcome, we can consider how innovative techniques can further the likelihood of success starting at the very earliest phases of procurement planning!

As we mentioned earlier, the Government often conducts market research by sending a Request for Information (RFI) to various industry members. A pre-solicitation conference is held, with industry invited to attend. Perhaps the Government releases a draft RFP and utilizes uses the feedback it receives to revise and finalize the RFP. There are usually one or more rounds of Questions and Answers after the RFP is released. As we discussed earlier, this process doesn’t deliver exactly what the Government wanted due to misinterpretations and other complications. As we know, however, many times after contracts are awarded, there are still technical (as well as other) questions that must be addressed.

Anyone who has participated in any of these activities knows how and why this occurs. The exchanges are usually tightly controlled and the communication is typically one way. Industry is asking the questions and the Government is not completely open in communicating its needs because it is risk averse. When the Government responds, the responses are often cryptic, leaving industry members to derive their own interpretation of the response.

There is negligible risk to the Government in having a dialogue about the what they’re trying to achieve. This could be done in a very open and transparent way using the innovative techniques that are part of our amazingly technological age. For example, there are a some great new organizations that facilitate multiparty participation in discussions (see https://www.innovationgames.com/budget-games-guide/) Imagine the Government project team (including the CO) having a pre-solicitation conference and inviting any interested vendor to help them acquire the best system possible. The Government could engage multiple industry professionals and clearly communicate what their budget is to get a better idea of the possibilities of what can be achieved in the timeline with their budget. When this is the basis for the dialogue, the chances significantly improve that the outcome of the development during execution will be realistic. The Government will have a much better understanding of what is possible, and thus be better able to evaluate actual performance. And, industry partners will have a better understanding of what the Government is trying to achieve. Additionally, all of this could be recorded and made available online for any interested bidder to review, adding to transparency in the process.

Several Government agencies are already increasing the use of innovation in the acquisition process. Specifically, the DHS Procurement Innovation Lab (https://www.dhs.gov/aiim) and U.S. Digital Services (USDS) (https://www.usds.gov/) are at the forefront of this effort and continue to vigorously promote innovative changes in acquisition while managing risk to the Government.

Part III: The FAR – Proscriptive or Prescriptive?

So, now we come to the big question: does the FAR allow that? The answer might surprise. The FAR actually promotes innovation!

It’s likely that many current Contracting Officers in the Government remember the last major FAR rewrite in the mid-90s. That revision introduced us to the concept of “best value” procurements (FAR 15). There may be a lack of understanding of the history of how FASA and FARA came about and what intent drove these reforms. Principally, the reforms were implemented so that the Government could act more like a business, rather than being bound to award a contract to the lowest bidder. The Government finally figured out that the cheapest solution was not always the best.

In FAR Part 7, which addresses acquisition planning, the FAR says the following (emphasis added):

7.102(b): This planning shall integrate the efforts of all personnel responsible for significant aspects of the acquisition. The purpose of this planning is to ensure that the Government meets its needs in the most effective, economical, and timely manner.

7.103 Agency-head responsibilities: Subpart (t) Ensuring that knowledge gained from prior acquisitions is used to further refine requirements and acquisition strategies. For services, greater use of performance-based acquisition methods should occur for follow-on acquisitions.

7.105 Contents of written acquisition plans: (a)(8) Acquisition streamlining. If specifically designated by the requiring agency as a program subject to acquisition streamlining, discuss plans and procedures to—

(i) Encourage industry participation by using draft solicitations, pre-solicitation conferences, and other means of stimulating industry involvement during design and development in recommending the most appropriate application and tailoring of contract requirements;

(ii) Select and tailor only the necessary and cost-effective requirements

Note that the FAR here does not limit what can be done to accomplish an efficient and effective procurement, nor does it limit the use of innovative techniques. This sounds good from a planning perspective, but what does the FAR say in Part 15 about exchanges with industry?

15.201 Exchanges with industry before receipt of proposals.

(b) The purpose of exchanging information is to improve the understanding of Government requirements and industry capabilities, thereby allowing potential offerors to judge whether or how they can satisfy the Government’s requirements, and enhancing the Government’s ability to obtain quality supplies and services, including construction, at reasonable prices, and increase efficiency in proposal preparation, proposal evaluation, negotiation, and contract award.

(c) Agencies are encouraged to promote early exchanges of information about future acquisitions. An early exchange of information among industry and the program manager, contracting officer, and other participants in the acquisition process can identify and resolve concerns regarding the acquisition strategy, including proposed contract type, terms and conditions, and acquisition planning schedules; the feasibility of the requirement, including performance requirements, statements of work, and data requirements; the suitability of the proposal instructions and evaluation criteria, including the approach for assessing past performance information; the availability of reference documents; and any other industry concerns or questions. Some techniques to promote early exchanges of information are—

(1) Industry or small business conferences;

(2) Public hearings;

(3) Market research, as described in Part 10;

(4) One-on-one meetings with potential offerors (any that are substantially involved with potential contract terms and conditions should include the contracting officer; also see paragraph (f) of this section regarding restrictions on disclosure of information);

(5) Pre-solicitation notices;

(6) Draft RFPs;

(7) RFIs;

(8) Pre-solicitation or preproposal conferences; and

(9) Site visits.

Note that the FAR does not say these are the only techniques or that the Government is limited to the techniques listed. Perhaps the acquisition officials interpreted this list as their only available options. Another equally valid interpretation would be that the FAR is suggesting possible alternatives, but not an exhaustive list. How could the authors of the FAR rewrite know all the possible techniques and technologies in the future that would improve acquisitions? It is likely they didn’t want to limit their choices to not be able to use better or more innovative techniques in the future.

Part IV: We are not Alone

In researching, we found videos from the Federal Acquisition Institute (FAI) on YouTube discussing this very topic! Here’s the link to their channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCpm8zq4WMhJi1pyXaXvuOfg

One video presents a Management Analyst discussing Acquisition Innovation Labs in “pockets” of the Federal Government from September 2017. The analyst mentions agencies having Acquisition Innovation Advocates as well. This is a positive sign that innovation is catching on.

While we are encouraged by the progress being made on this front, it is not going far enough (note the promotion of “structured exchanges”) and still focuses on defining requirements in the planning stages. Additionally, there is a continued focus solely on the acquisition itself and not the outcome of contract performance. Our recommendations are for the Government to use the value it obtains from the awarded contract as the basis for evaluation of the acquisition process, rather than just awarding a contract more quickly. While that is an admirable goal, a shortened period to award a contract doesn’t necessarily provide a successful outcome on completion of the contract.

Part V: Special Contract Considerations around Agile

One of the defining aspects of Agile software development is the “sprint.” For those not familiar with Agile software development, a sprint is a two-week cycle where enhancements to the system are the focus of the team all the way through release (including coding, testing, User Acceptance). The team has a daily stand up (a brief meeting) to address progress made and focus for the day. Any problems (“blockers”) are brought up so that team members can collaborate to resolve issues. We believe that a sprint can serve as the basis for a fixed price performance-based contract type. It may also be beneficial to include an incentive fee based upon outcomes using the achievement of the Government’s vision, value to the Government and quality as measures. This creates greater motivation to pursue the highest value enhancements and reduce bugs in each release.

The fixed-price contract format has other advantages for the Government. Cost-based contract types are not suitable for all possible contractors, since many may not have an approved accounting system for cost type contracts. Time & materials format contracts may not provide sufficient incentives to ensure the Government receives quality and valuable results from the money it has expended.

From an industry perspective, a main concern is having a consistent number of sprints for staff utilization planning. As mentioned earlier, Agile systems acquisition is acquisition of services, not systems. Therefore, to avoid unacceptable level of risk, industry would desire a predictable stream of revenue to properly staff the project and avoid gaps where their staff is not sufficiently involved and thus becomes an extra overhead cost. In addition, Industry would likely want some level of objectivity in any incentive fee scenario to avoid too much subjectivity in the evaluation.

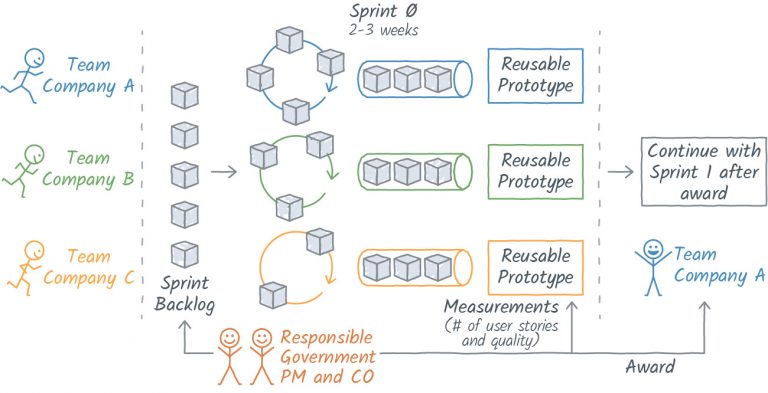

One potential option would be to require bidders to complete one sprint as the technical evaluation instead of a written proposal or orals. The benefit is the Government could see actual work product instead of reading or hearing about it. This changes the dynamic to “show me” instead of “tell me.” (Oral presentations only benefit a company that can be coached the best on how to present). If the requirements were well developed in the acquisition process, contractors could complete a distinct segment of the work in a normal sprint cycle. The Government could then evaluate the value and perform UAT to determine the actual number of defects in the software delivered during “sprint 0.”

Since the Government would be awarding FP/IF type task orders under a single award IDIQ, Sprint 0 would be the basis for the sprint pricing which gets the Government a faster start to the program instead of waiting for Sprint 0 to be completed. Bidders would all propose their price to complete every sprint based on the cost to accomplish Sprint 0. The Government could use the criteria it establishes in the incentive fee calculation to rate each offer. The pricing could be submitted within 30 days after Sprint 0 is complete – it would not necessarily need to be submitted at the same time. This approach also allows each bidder to review the level of effort it took to accomplish the sprint to estimate the FFP more accurately.

An additional benefit of this approach is that evaluation of an actual product would be easier and more objective than evaluation of a written technical proposal. Best value will be clearer based upon what was delivered for the price in sprint 0. If one product has more features or is further developed than another for approximately the same price, the award decision could be easier and faster. In addition, the Government would also have the benefit of the first sprint being completed. The result from Sprint 0 from winning team would be reused to bootstrap and continue to build the system, shortening the timeline to achieving measurable results.

We also recommend that agile procurements have shorter contract durations. Determining the actual duration could be part of the pre-solicitation discussions (remembering the future) on how long the system would take to develop to achieve the outcomes envisioned during the exercises.

Figure 4: Example Agile Acquisition Sprint 0

PART VI: Conclusions

It makes some sense for the Government to be risk averse – doing so protects tax dollars against waste. However, techniques used in acquisitions in the past were not always successful in obtaining systems, wasting time and taxpayer money. The Government realized this in the 1990s with FASA and FARA reforms, and is it making positive and substantive steps toward spending less time and money acquiring goods through the FAR, but there are still significant changes that need to be implemented by senior agency leadership and acquisition professionals.

First is to define a successful acquisition by the value of the final product delivered – reverse plan from the end of the contract all the way to pre-solicitation activities and define a successful acquisition by using measurable results from the final product delivered. The acquisition and contract performance are intrinsically connected. By envisioning the successful, measurable outcomes at the end of the contract and incorporating actions that will help the Government achieve them as part of the acquisition process, the Government will increase its probability of success. Part of that process should be for potential contractors to show that they can perform, not just say they can.

Next, OMB’s Office of Federal Procurement Policy (OFPP), the General Services Administration (GSA), and the Federal Acquisition Institute (FAI) should promote greater innovation and industry engagement as best practices to achieve the goals during the pre-solicitation planning process. Most Contracting Officers will not take the initiative to innovate seriously unless they have support from senior Government leaders. There is too little incentive to do so. OFPP should tell more of the acquisition community that the FAR is not standing in the way of the use of innovation in acquisition. Conversely, OFPP, GSA and FAI should be the ones to fully implement the reforms envisioned by FASA and FARA in the 90s. FAI should aggressively promote the idea that program success is the goal of all acquisitions, not the award of a contract.

Finally, the OFPP should emphatically and energetically reprioritize program success as its highest priority – ensuring that all Contracting Officers view program failure is the highest risk to the Government – greater than any other conceivable risk. We believe that program failure results in more waste of taxpayer funds than fraud by those outside government, and corruption by those within. An acquisition workforce that is engaged from the end to the beginning – one that does not feel constrained but empowered by the FAR – would increase the likelihood of program success.

About the Authors

- Kevin White is director of contracts for REI Systems with experience in both government and commercial contracting.

- Gissa Sateri is a business development director at REI Systems with experience in operations and general management, capture management, strategic planning and IT consulting.

- Pawin Chawanasunthornpot is a solution architect at REI Systems who is passionate about the agile approach.